According to this.

But what’s Ubuntu Aubergine?

According to this.

But what’s Ubuntu Aubergine?

The “good enough is good enough” culture is bullshit.

Ever since my impatient and juvenile deconstruction of the new “light” GTK themes for Ubuntu Lucid, there’s been a lot of talk elsewhere, as well as some more clues about the new interface.

First came Mark Shuttleworth’s announcement on the rebranding. Something that seems to have been overlooked, most likely because of its ambiguous wording, is his mention of a new desktop font:

We have commissioned a new font to be developed both for the logo’s of Ubuntu and Canonical, and for use in the interface. The font will be called Ubuntu, and will be a modern humanist font that is optimised for screen legibility.

It sounds here like he’s only talking about one font: the logo font we’ve already seen some of. But “for use in the interface”? Unless he’s talking about having two variants within the same family known as “Ubuntu,” it doesn’t seem that this logo font will translate well to menus and buttons. Here’s hoping they’re developing something a little more pleasant than DejaVu Sans, whose bulkiness has long been a cause for ire among Ubuntu users. And although I’ve always found it to be rather nice (provided that it’s bumped down a size), I don’t doubt that the artwork team could come up with something that exceeds it.

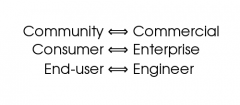

Maybe the most positive thing to come out of Shuttleworth’s announcement is his explanation behind the logic of the two colors, orange and aubergine. These two colors, as well as some other visual cues, are the vocabulary used to distinguish between the different applications and users of Ubuntu. It’s clear that a lot of thought went into this design vocabulary, and, as many have said, the new website mockup and other miscellany, such as the CD case and concepts for signage, are pretty much home runs for Canonical’s art team. It doesn’t approach perfection, by any means, but it’s far more than any of us probably imagined to be possible. For that they deserve enormous acclaim.

Maybe the most positive thing to come out of Shuttleworth’s announcement is his explanation behind the logic of the two colors, orange and aubergine. These two colors, as well as some other visual cues, are the vocabulary used to distinguish between the different applications and users of Ubuntu. It’s clear that a lot of thought went into this design vocabulary, and, as many have said, the new website mockup and other miscellany, such as the CD case and concepts for signage, are pretty much home runs for Canonical’s art team. It doesn’t approach perfection, by any means, but it’s far more than any of us probably imagined to be possible. For that they deserve enormous acclaim.

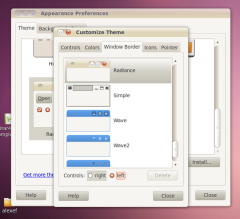

Sadly, far too much of the conversation around this redesign has been focused on the new default button placement. It’s an interesting choice, one that I’m sure they wouldn’t make lightly, and it would be valuable to have a discussion about the merits of different button placements — a discussion that consisted of something other than “WAHHHHH MAC ZOMG BUTTON FAIL.”  GNOMEr Ivanka Majic mercifully explained some of the reasoning behind this decision in a recent blog post, and there are valid arguments to be made for all kinds of different approaches — in fact, in my opinion they’ve got it wrong. But it warmed my heart a little bit to read Mark Shuttleworth’s response to this bug report (as pointed out by Web Upd8):

GNOMEr Ivanka Majic mercifully explained some of the reasoning behind this decision in a recent blog post, and there are valid arguments to be made for all kinds of different approaches — in fact, in my opinion they’ve got it wrong. But it warmed my heart a little bit to read Mark Shuttleworth’s response to this bug report (as pointed out by Web Upd8):

The issue is not a bug, it’s a difference of opinion on what is the best result. We may change it, or we may hold it.

Fuck yes! You tell ’em, Mark. For as much complaining as I’ve done about the aesthetics of this new desktop theme, “usability” is much more a science (though still inexact), and if you believe that these new button locations are more rational, and that people will ultimately benefit from them, then by all means, yes, do it. It’s that kind of (relatively) bold experimentalism that makes me think they’ve got some balls after all.

And please, guys, please don’t ask for this to be made into another option. This same thing happened when everybody started bitching about Karmic’s new Notify-OSD behavior. Obviously option-bloat presents several technical problems, but it’s philosophically unsound, as well; it’s the easy way out. Here’s what Mark had to say on the matter:

And please, guys, please don’t ask for this to be made into another option. This same thing happened when everybody started bitching about Karmic’s new Notify-OSD behavior. Obviously option-bloat presents several technical problems, but it’s philosophically unsound, as well; it’s the easy way out. Here’s what Mark had to say on the matter:

In Ayatana, we’ll take an opinionated stance, and we’ll apply some common principles to the design process, and we’ll live with the results.

I have no interest whatsoever in making it possible for anybody to have any environment they want – we already have that. I’m interested in driving forwards to build a default out of the box experience which is as good as we can make it for the new, consumer user.

Meanwhile, even a blog as important as Web Upd8 is plagued by this attitude:

But I’m putting my money on the fact that nothing will be done regarding this. Why? If Ubuntu copy the OS X theme, they must really like Apple, right? The secret announcement of the new theme that came in the last day of the UI freeze and all that was also something very Apple-ish. Well then, just like Apple, they won’t listen to what the users want and will do things their way. The only difference is Ubuntu was supposed to be open. But I really hope I’m wrong!

First, this represents a grave misunderstanding of the word “open.” Second, “listening to what the users want” is impossible. Which users? On which issues? Whose wants are determined in what way? This is not productive discussion. Nor is this:

There is no particular reason for moving them to the left, it’s change for the sake of change

I can forgive someone for not having read any of the rationale behind the new button placement, but to assume so hastily that it was an arbitrary decision is unfair and closed-minded.

There’s of course plenty more to be said, but I’ll wrap up here with two quotes, the first from Mark Shuttleworth:

Experiments are also not something we should do lightly. The Ubuntu desktop is something I take very personally; I feel personally responsible for the productivity and happiness of every Ubuntu user, so when we bring new ideas and code to the desktop I believe we should do everything we can to make sure of success first time round. We should not inflict bad ideas on our users just because we’re curious or arrogant or stubborn or proud.

And, finally, Máirín:

Some folks understandably believe art and design are stuffs enshrouded in a mysterious haze of incense smoke without much logic or reason involved. I get it. I’ve been there too, and I think it’s easy to feel that way — discussions about art works sometimes get a bad reputation for being anywhere from fussy, to bizarre, to completely pointless.

You may find solace in the fact that there’s actually plenty of logical principles and elements and a vocabulary for them that can be use to discuss such works in a productive manner that doesn’t involve ‘invoking an embodiment of emotive symbolism’ or similar. I strongly recommend you explore some of this vocabulary, as not only will it help you more effectively communicate your critique but reading through a brief survey of basic design principles will probably even help you explain why you feel a particular way about an element of a work you’re critiquing.

Even a couple years ago, video editing wasn’t considered an essential part of a desktop, for most users. It was the realm of professionals and hobbyists who could afford the necessary hardware to transcode video in less than an hour.

But after the advent of YouTube, adequate processors, and ubiquitous cameras — in phones, monitors, and now on the iPod nano — everybody feels that it’s their right to add scrolling text and wipes to their little movies. And rightly so; video editing software has long been expensive and difficult for a reason. But it’s almost 2010, and that shouldn’t be the case anymore. It’s no longer too much to expect to be able to put a title and a fade-out on a video where you complain about your hair, even if it is a trivial indulgence. You don’t need to know HTML to run a blog; why should you need to learn scripting languages and FFmpeg switches to run a vlog?

Steve Jobs was famously mistaken in thinking that the next step for personal computing at the turn of the century was video editing, until it took a backseat while Napster made digital music and the iPod the most prominent technologies of this decade. And as all that went on, processors got outrageously fast, and hard drives got outrageously large, even in “low-end” systems. iMovie existed, but has only recently become familiar and comfortable to large numbers of people. Microsoft’s answer to iMovie, “Microsoft Windows Video Editor 1.3” or whatever it must have been called, was feeble, buggy, and went unused as most PC owners had to work hard to derive anything of value from it; iMovie, meanwhile, practically asked Mac owners to use it. It’s my understanding that Microsoft’s video editor has improved lately, but I don’t know for sure.

Anyway, so here we are, with video editing taken for granted by some, and indignantly demanded by others. And, while we’re at it, a relatively large migration toward Ubuntu. 8.10 Intrepid was a landmark release, 9.04 followed suit, and 9.10 is becoming unequivocally the most anticipated Linux distribution by the general populace ever. Even in its beta form it’s being called “almost perfect,” and generally heralded everywhere not only as a triumph of open-source, but as a triumph of operating systems period.

There’s more to life than hard, sterile pragmatism, and if you think otherwise, you are cold and dead and nobody will ever love you.

So!, with all these people working to make Linux accessible, surely they’ve got some decent video editor up their sleeves? Well — as is a typical answer from most Linux users — yes and no. There is Cinelerra, which is very powerful and enjoys a wide user base, but even its manual admits to its Linux heritage, that “Cinelerra is not intended for consumers.” I can attest to this. In addition to Cinelerra I’ve downloaded just about every video editor there is for Linux, from Avidemux to Kdenlive to Kino to PiTiVi. All of them either crash in Ubuntu, are terrifically complicated, or lamentably simple. Simply put, there is no “iMovie for Linux.”

But this is precisely what Mark Shuttleworth is shooting for with Ubuntu. Or, rather, it’s a good metaphor for what he’s shooting for — to make Linux not merely easier to use than other distros, but to be inviting to people who don’t even know what Linux is. This is why Ubuntu’s slogan — “Linux for human beings” — has become so obsolete. Of the things that Linux provided when the Ubuntu project began in 2004, Ubuntu now provides them in a more accessible way than they’ve ever been provided, and if a person has heard of only one Linux distro, it is likely to be Ubuntu.

Now, however, with Shuttleworth explicitly taking aim at Apple, Ubuntu’s slogan — not merely for marketing purposes, but for the underlying vision of the project as a whole — needs to evolve. “Linux for human beings” begins with the premise of Linux, and qualifies it with the promise of ease-of-use. In order to gain the significant market share that Shuttleworth wants to see, and to properly orient Ubuntu’s developers toward that end, the “Linux” part of Ubuntu needs to be secondary. What must instead be emphasized is that it is a powerful, easy, fun, and free operating system that happens to use a Linux kernel.

These things are becoming increasingly true, but, as much as I am impressed by it, I can’t in good conscience say that Karmic fulfills the ultimately desired promise of Ubuntu. Karmic is still just “Linux for human beings.”

At the same time, never before has this promise been more clearly within view. Several huge — huge — things have happened recently, or are happening, to take Ubuntu beyond its current status as merely the best Linux distro, from an eccentric “third-party candidate” to a genuine competitor. Aside from its hugely increased hardware support out-of-the-box (which, bravo), I’m tempted to argue that the improved font rendering in Jaunty is the single most important step in increasing Ubuntu’s appeal — and further that anybody who disagrees with me is hopelessly out of touch with the real world.

Linux users pride themselves on withstanding the most brutal of computing environments, but it’s that kind of egotism that, if unchecked, will prevent Linux from ever gaining on the desktop. If you think pretty wallpapers are a frivolous waste of your disk space, that’s your prerogative — but if you think that it was a bad decision for Canonical to include them in Karmic, given all that they’re trying to accomplish, then you’re not paying attention. There’s more to life than hard, sterile pragmatism, and if you think otherwise, you are cold and dead and nobody will ever love you.

I have a couple rants-in-waiting about Ubuntu. This guy says everything I could say way better than me. Go read his blog.

As shown here and here, among other places:

Some positives are that the new Humanity icon theme is a great improvement, and that the font rendering continues to impress.

One of the first things I noticed after booting into Ubuntu 9.04, Jaunty Jackalope, is that Google Reader and Gmail looked a bit off. I quickly realized they were both using different sans-serif fonts than they had previously (Nimbus Sans), despite Firefox’s preferences having Nimbus set as the default sans.

I knew that Google isn’t so great with their stylesheets, in some cases declaring a font-family of just “Arial,” with no “sans-serif” backup in the font-stack (which would, of course, let Firefox substitute in whichever default sans the user had set – in my case, Nimbus).

I also knew through playing around with ~/fonts.conf that Linux allows you to define substitutions for different font names. It was my hunch that there was something new about Jaunty (which has been praised for its better presentation of text) that defined Liberation Sans – the font I determined I was looking at – as the preferable substitute for Arial.

After looking around a bit I found the culprit in /etc/fonts/conf.avail/30-metric-aliases.conf. Around line 182 you should see the beginning of a section devoted to the Microsoft typefaces, and shortly under that (around line 186), the line:

<family>Liberation Sans</family>Just above that, insert the following line:

<family>Nimbus Sans L</family>Reboot your system, and when you’re back up, Ubuntu should now replace any calls for Arial with Nimbus Sans.

Of course, this should only be done if you prefer Nimbus Sans. It’s been claimed that Liberation Sans is better hinted than either Nimbus or FreeSans, and from the looks of things, it is. Still, I just prefer Nimbus. That serif on the upper-case ‘J’ in Libertine especially bothers me.

I still love Linux Libertine as a Times substitute, however.