Even a couple years ago, video editing wasn’t considered an essential part of a desktop, for most users. It was the realm of professionals and hobbyists who could afford the necessary hardware to transcode video in less than an hour.

But after the advent of YouTube, adequate processors, and ubiquitous cameras — in phones, monitors, and now on the iPod nano — everybody feels that it’s their right to add scrolling text and wipes to their little movies. And rightly so; video editing software has long been expensive and difficult for a reason. But it’s almost 2010, and that shouldn’t be the case anymore. It’s no longer too much to expect to be able to put a title and a fade-out on a video where you complain about your hair, even if it is a trivial indulgence. You don’t need to know HTML to run a blog; why should you need to learn scripting languages and FFmpeg switches to run a vlog?

Steve Jobs was famously mistaken in thinking that the next step for personal computing at the turn of the century was video editing, until it took a backseat while Napster made digital music and the iPod the most prominent technologies of this decade. And as all that went on, processors got outrageously fast, and hard drives got outrageously large, even in “low-end” systems. iMovie existed, but has only recently become familiar and comfortable to large numbers of people. Microsoft’s answer to iMovie, “Microsoft Windows Video Editor 1.3” or whatever it must have been called, was feeble, buggy, and went unused as most PC owners had to work hard to derive anything of value from it; iMovie, meanwhile, practically asked Mac owners to use it. It’s my understanding that Microsoft’s video editor has improved lately, but I don’t know for sure.

Anyway, so here we are, with video editing taken for granted by some, and indignantly demanded by others. And, while we’re at it, a relatively large migration toward Ubuntu. 8.10 Intrepid was a landmark release, 9.04 followed suit, and 9.10 is becoming unequivocally the most anticipated Linux distribution by the general populace ever. Even in its beta form it’s being called “almost perfect,” and generally heralded everywhere not only as a triumph of open-source, but as a triumph of operating systems period.

There’s more to life than hard, sterile pragmatism, and if you think otherwise, you are cold and dead and nobody will ever love you.

So!, with all these people working to make Linux accessible, surely they’ve got some decent video editor up their sleeves? Well — as is a typical answer from most Linux users — yes and no. There is Cinelerra, which is very powerful and enjoys a wide user base, but even its manual admits to its Linux heritage, that “Cinelerra is not intended for consumers.” I can attest to this. In addition to Cinelerra I’ve downloaded just about every video editor there is for Linux, from Avidemux to Kdenlive to Kino to PiTiVi. All of them either crash in Ubuntu, are terrifically complicated, or lamentably simple. Simply put, there is no “iMovie for Linux.”

But this is precisely what Mark Shuttleworth is shooting for with Ubuntu. Or, rather, it’s a good metaphor for what he’s shooting for — to make Linux not merely easier to use than other distros, but to be inviting to people who don’t even know what Linux is. This is why Ubuntu’s slogan — “Linux for human beings” — has become so obsolete. Of the things that Linux provided when the Ubuntu project began in 2004, Ubuntu now provides them in a more accessible way than they’ve ever been provided, and if a person has heard of only one Linux distro, it is likely to be Ubuntu.

Now, however, with Shuttleworth explicitly taking aim at Apple, Ubuntu’s slogan — not merely for marketing purposes, but for the underlying vision of the project as a whole — needs to evolve. “Linux for human beings” begins with the premise of Linux, and qualifies it with the promise of ease-of-use. In order to gain the significant market share that Shuttleworth wants to see, and to properly orient Ubuntu’s developers toward that end, the “Linux” part of Ubuntu needs to be secondary. What must instead be emphasized is that it is a powerful, easy, fun, and free operating system that happens to use a Linux kernel.

These things are becoming increasingly true, but, as much as I am impressed by it, I can’t in good conscience say that Karmic fulfills the ultimately desired promise of Ubuntu. Karmic is still just “Linux for human beings.”

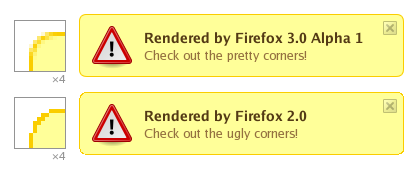

At the same time, never before has this promise been more clearly within view. Several huge — huge — things have happened recently, or are happening, to take Ubuntu beyond its current status as merely the best Linux distro, from an eccentric “third-party candidate” to a genuine competitor. Aside from its hugely increased hardware support out-of-the-box (which, bravo), I’m tempted to argue that the improved font rendering in Jaunty is the single most important step in increasing Ubuntu’s appeal — and further that anybody who disagrees with me is hopelessly out of touch with the real world.

Linux users pride themselves on withstanding the most brutal of computing environments, but it’s that kind of egotism that, if unchecked, will prevent Linux from ever gaining on the desktop. If you think pretty wallpapers are a frivolous waste of your disk space, that’s your prerogative — but if you think that it was a bad decision for Canonical to include them in Karmic, given all that they’re trying to accomplish, then you’re not paying attention. There’s more to life than hard, sterile pragmatism, and if you think otherwise, you are cold and dead and nobody will ever love you.

The first two advantages are things you almost never need to do with music libraries. And the third has been supplanted by now-ubiquitous search boxes: if you know what you’re looking for, you search; and if you don’t, an alphabetized list is not the way to find it.

The first two advantages are things you almost never need to do with music libraries. And the third has been supplanted by now-ubiquitous search boxes: if you know what you’re looking for, you search; and if you don’t, an alphabetized list is not the way to find it.